Translator’s Notebook: April

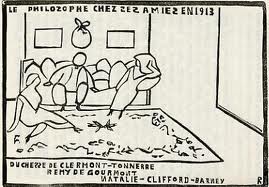

April is said to be the cruelest month. And so it was for Renée Vivien in 1909, when, towards the end of the month, the poet Lucie Delarue-Mardrus gave a supper party for Natalie Barney that would change Vivien’s life forever.

And not for the better.

Forget everything you thought you knew about April in Paris

The biography I’m translating, Élisabeth de Gramont by Francesco Rapazzini, has upended everything I thought I knew about that fateful April in Paris 1909. Shortly after Lucie introduced Barney to her childhood friend Lily de Gramont, the (very married) Marquise de Clermont-Tonnerre, they became lovers like two flames leaping together, “free as fire.” Sexual awakening with a soulmate served up an intensity Lily had never known, one Natalie hadn’t tasted herself…since her starcrossed affair with Vivien.

All through that spring and summer, it was a season of wonder and sensuous delight for Lily. For Renée Vivien, not so much. By July, she would be penniless and hanging on to life by a thread, relying on the sole support of Lily’s cousin, Hélène de Rothschild. In November, she would be dead. Of suicide.

Until now, and for more than 50 years since Élisabeth’s own death, key dates of 1909 and their portentious events were unknown to some of the world’s best belles-lettres biographers.

Rewriting the history of the grandes dames by translating French to English: exciting stuff.

My adventures in translating have also led me to one of Vivien’s more sympathetic and sensitive interpreters, the filmmaker Jane Clark, who wrote and directed a sexy short film about Vivien.

Renée Vivien? Who’s she?

For those of you who don’t know the radical poetry or the tragic legend of Renée Vivien, she was born Pauline Tarn in London in 1876. Her mother was an American from my home state of Michigan. Her father inherited a Scottish merchant legacy and died when Renée was a little girl.

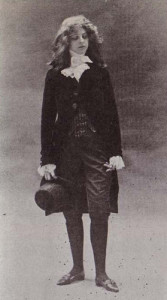

Having spent the happiest years of her childhood in France, she endured a traumatic adolescence–some of it under lock and key–dominated by her abusive mother until, at 21, Renée finally inherited the fortune that allowed her to return to Paris and dedicate her life to poetry. She wrote exclusively in French. If that wasn’t radical enough, she dressed like Hamlet. Taking it to the limit, she rejected male-dominated institutions and did her best to retire from society that would never accept her uncompromising feminism. This didn’t do much to discourage her fans, so Vivien resorted to hiring impersonators to stand in at her own poetry readings. She translated Sappho from the famous Greek fragments that had only recently been discovered among the rubbish heaps excavated at Oxyrynchus.

In America, her poetry is as unknown today as Sappho’s was then. In France, she’s a big deal.

In 1899, the virginal Vivien met the worldly Natalie Barney at the theatre. It was a coup de foudre. Vivien knew right away her life would never be the same.

It wasn’t. The lively Barney, already a master of the seductive arts and sciences at 24, was reeling from a scandalous grande passion with the Angelina Jolie of her era, the courtesan Liane de Pougy. Basically, Barney had just been dumped by the world’s most desirable woman. Turns out, Pougy had not wanted to be saved from prostitution after all. Barney wasn’t just heartbroken. She was humiliated.

But where does a young Don Juan go after Angelina Jolie? Such were Barney’s thoughts, clutching the “Dear John” letter while riding through the Bois de Boulogne in her coach, when Renée began to recite one of her poems. Beauty in all its forms would always get Barney’s complete attention. And so it did that day in 1899.

Now she put heart and soul into redirecting what biographer Diana Souhami calls Vivien’s “longing to be dead.” The two young women began their mismatched love affair in dizzying purity with poetry on their lips, kneeling before one another in a room stuffed with blazing candles and overblown lilies. But Barney’s faithless passion had awakened more than puppy love in Vivien, who was already a chloral hydrate addict by that time. I have never seen the edgy, impetuous, dangerous side of Viven’s character portrayed so well as how it is channeled, rather than merely acted, by Traci Dinwiddie in THE TOUCH. Necar Zadegan does a good job with Kérimé Turkhan Pasha, too. Their chemistry is incredible. You can rent the eight-minute film here for a nominal fee on Filmbinder.

Past is prologue

Los Angeles-based writer/director Jane Clark is also the producer behind the longest screen kiss in film history. While making gritty, topical films like that one (ELENA UNDONE, dir. Nicole Conn 2010) and METH HEAD, now touring the festival circuit, she seeks out character-driven stories in all genres, including romance. One of my favorite genres, too. Clark predicts it will soon undergo a major resurgence, with possibilities opening up in all directions as younger audiences bring their broadened minds to the movies along with their buying power. Will that mean more (and better!?) period dramas and romances about The Lost Generation and their forebears? I hope so.

I’ll publish my conversation with Jane Clark in the days to come. In the meantime, I hope you enjoy THE TOUCH. It’s a slice of life gone by: a furtive meeting in Paris, a moment of stolen passion that took place between a besotted poet and a beautiful Turkish Vizier’s wife living in seclusion in 1906. (Kérimé’s husband, Turkhan Pasha, formerly Foreign Minister of the Ottoman Empire, had come to Paris in 1899 as head of the Turkish delegation to the Peace Conference that followed the Treaty of Paris.) Jane Clark bases her film on this gorgeous, sexy poem. It out-Beaus Beaudelaire, don’t you think?

The Touch

The trees have kept some lingering sun in their branches,

Veiled like a woman, evoking another time.

The twilight passes, weeping. My fingers climb,

Trembling, provocative, the line of your haunches.

My ingenious fingers wait when they have found

The petal flesh beneath the robe they part.

How curious, complex, the touch, this subtle art—

As the dream of fragrance, the miracle of sound.

I follow slowly the graceful contours of your hips,

The curve of your shoulders, your neck, your unappeased breasts.

In your white voluptuousness my desire rests,

Swooning, refusing itself the kisses of your lips.Renée Vivien